Team-Based Learning

Team-based learning (TBL) is a pedagogical approach that focuses on the use of student teams completing group assessments and assignments throughout the semester. It’s more than just group work, it’s a collaborative strategy used to increase student motivation and encourage a deeper level of student engagement with the course material.

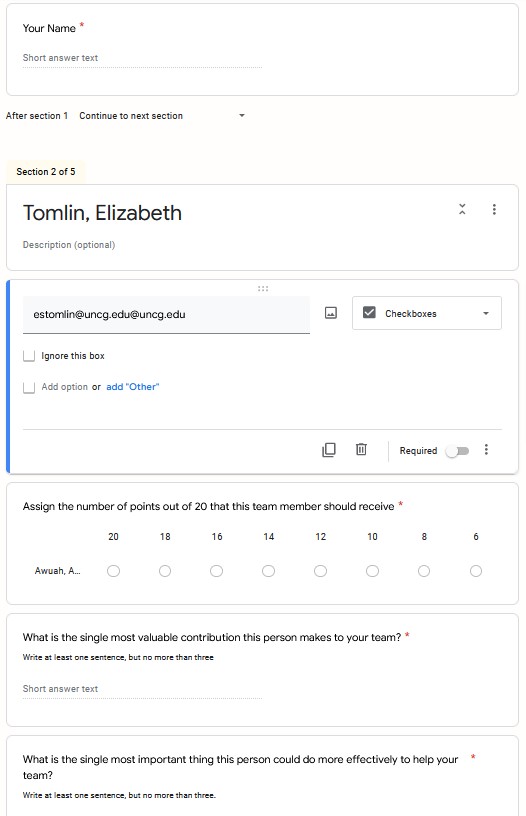

Special thanks to Dr. Elizabeth Tomlin for her work in creating this content for UNCG faculty. Throughout this section, she references specific examples of her use of Team-based learning from her UNCG courses.

Overview of Team-Based Learning

A teaching strategy where groups of students work as a cohesive team to apply course content to solve problems together. Team-based learning (TBL) differs from “doing group work” in a class mainly because it makes use of a specific organizational structure and focuses on decision-based assignments. In a TBL class, there is more focus on group work where students apply course concepts to solve problems than the instructor lecturing.

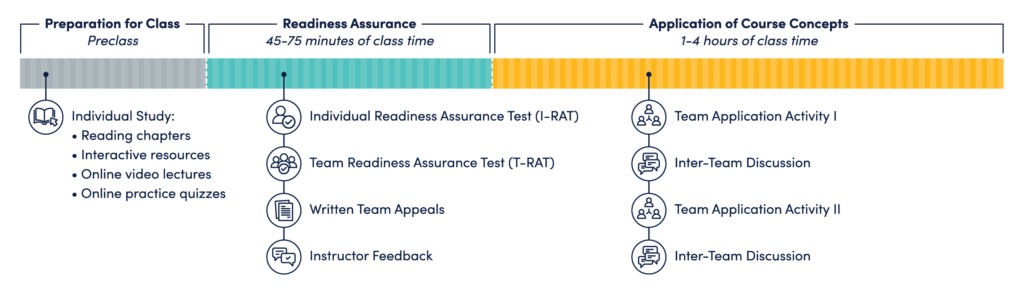

TBL courses are organized into units where each unit follows this activity sequence.

According to Michaelson & Sweet (2008), There are 4 elements that need to be managed successfully in a TBL class:

- Groups – Groups must be properly formed and managed.

- Feedback – Students must receive frequent and timely feedback. In addition to peer feedback, the Readiness Assurance Process (RAP) provides immediate feedback to students.

- Accountability – Students must be accountable for the quality of their individual and group work. One way this is achieved is through peer feedback

- Assignment Design – Group assignments must promote both learning and team development.

Elizabeth Tomlin recommends that we consider a 5th element to this description, which is providing appropriate materials with learning objectives for Pre-class individual study. Pre-class individual study requires that students be provided with organized and high quality materials aligned with learning objectives for them to work through ahead of class. This means that a team based learning class is essentially a flipped classroom. The flipped class format is applicable to in-person, online, hybrid and hyflex classes.

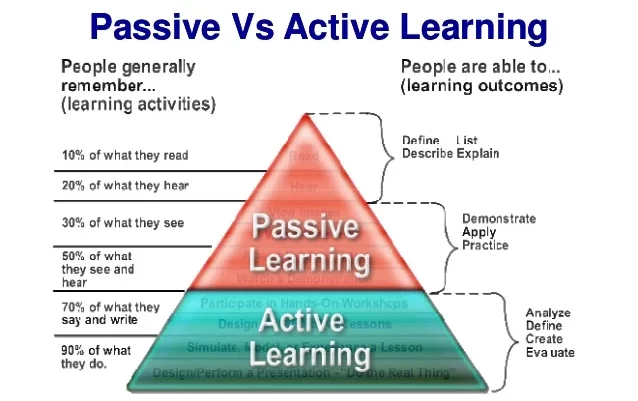

Team-based learning (TBL) involves active cooperation between students rather than simply listening to a lecture. Knight & Wood (2005) summarize some of the data that show that lecturing is a fairly ineffective pedagogical tool and demonstrate that active learning improves learning outcomes in a large biology class. In recent years, we have all seen that the attention span of students when it comes to lectures is getting shorter, and they are frequently off task and on their phones rather than being focused on class. This is true in both lecture and laboratory settings.

Pollack (2018) reported that the use of TBL in a neuroscience course resulted in overall more regular attendance and higher exam scores. Students explained, listened and debated and felt responsible to their teammates to prepare for and come to class regularly. Similarly, Koles et al. (2010) found that team-based learning resulted in 5.9% higher mean scores achieved by second year medical students on pathology based content. Freeman et al. (2014) saw not only gains in exam performance, but found that students in classes with traditional lecturing were 1.5 times more likely to fail than in classes with active learning. This data is based on a metaanalysis of 225 studies on active learning in science, engineering and mathematics.

This type of cooperative learning is not only beneficial for lower achieving students but also benefits the higher achieving ones. When students explain things to each other, they are not only reinforcing their own learning but finding the “edges” of what they know. We have all had the experience of being pretty sure we know something but then find ourselves unable to explain in detail when questioned. Working through problems together allows students to find areas where they have misconceptions. Students are more likely to accept and retain complex concepts when they participate in the construction of the knowledge themselves (Handelsman et al. 2007).

Problem-based learning in teams gives faculty members a better understanding of WHY students might have chosen a wrong answer by focusing on the students’ words. Students spend class time reflecting and sharing about why they chose their answers on team tests rather than just what they chose, and debating the reasons for decisions on team assignments. This reflective practice benefits the student directly, but also gives faculty members insight on how to revise some aspects of content delivery, addition of different homework assignments and team activities that target areas of misconception more effectively.

Readiness Assurance Test (RAT)

The readiness assurance process is extremely important to provide students with the opportunity to be as prepared as possible to work on group assignments together. In addition, the process of explaining why they chose their answers on the team portion of the test is a powerful learning opportunity. Testing has been demonstrated to not only be a way of assessing learning, but also as a way of improving it (Roediger & Karpicke 2006).

Elizabeth Tomlin explains how she uses this process:

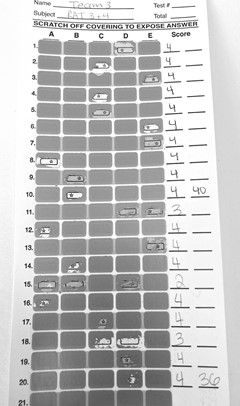

The process starts with students taking a closed book individual readiness assurance test (iRAT). I give 10 multiple choice questions and allow about 10-12 minutes. Students then turn in their individual test and start working on the team readiness assurance test (tRAT). The team test is identical to the individual test except the students use scratch off cards to answer the questions. I give students as much time as they need, and don’t impose a deadline until most of the teams are done. I fit two tRAT’s on each 25 question card.

The IF-AT scratch off cards come with an answer key, so you match your test to the answers preset on the cards. Students discuss each question and then scratch off the letter choice that they agree on. If they are correct on the first attempt they get 4 points. For every wrong choice scratched they lose 1 point.

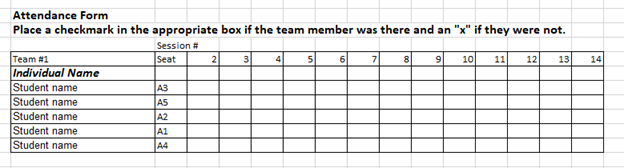

I provide a pocket folder for each team which contains an attendance form, an iRAT for each team member on white paper, one copy of the tRAT on colored paper and a scratch off card.

Students take attendance so that I know who gets credit for the team test. This usually matches the individual tests submitted, but sometimes students show up late and choose to forfeit the iRAT in favor of taking the team test.

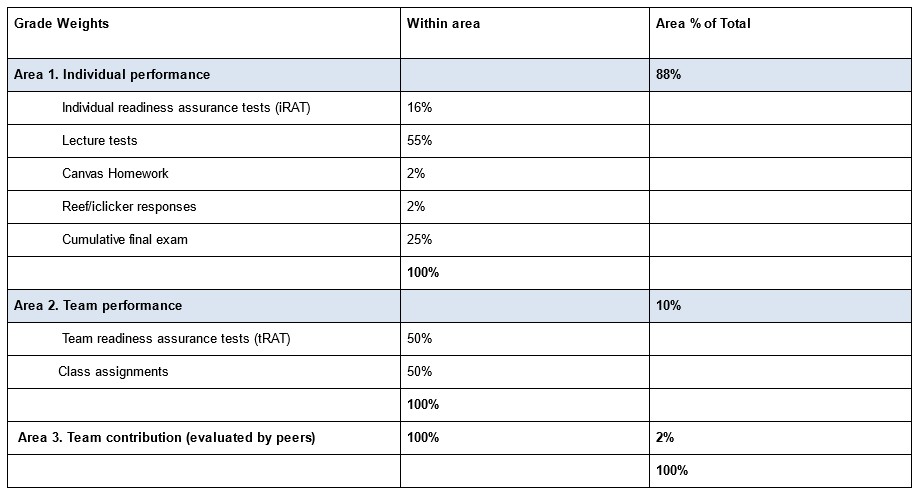

The iRAT’s have a greater direct impact on a student’s grade than the tRATs, but tRATs provide a better opportunity for learning.

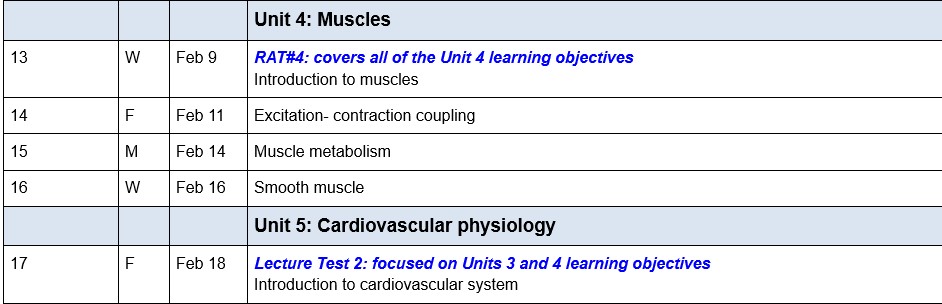

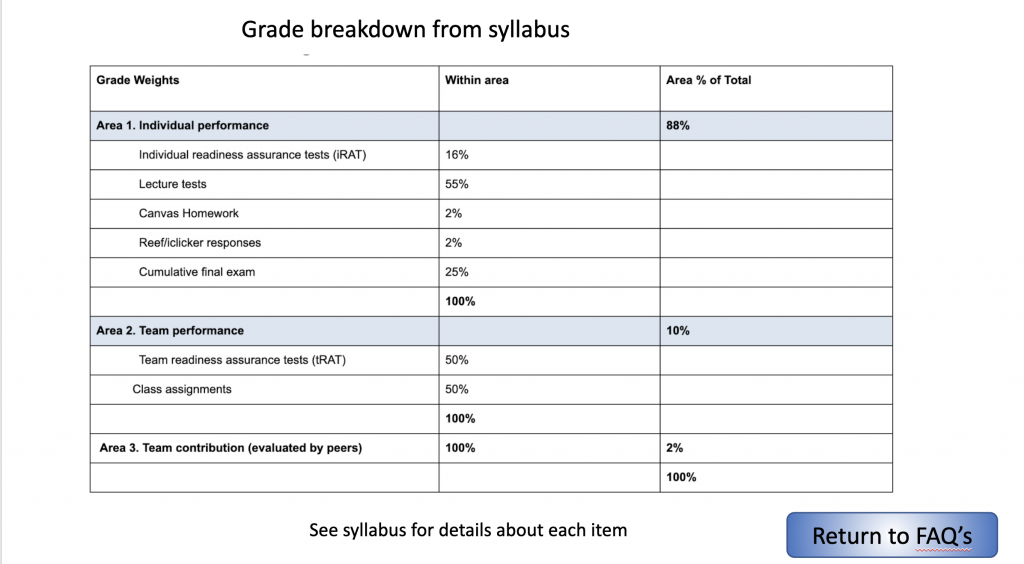

The table below is the grade breakdown for my class. I want a student’s final grade to be very close to the average of their 4 summative lecture tests, and this distribution works well. I give 10 RAT’s and about 16 team assignments in addition to the 4 summative lecture tests and final exam, so students have lots of room to improve their grade if they have a rocky start. The frequent testing in this class is important as it is a very cumulative subject.

Larry Michaelson talks about providing an appeal process on iRATs where teams can provide a written rebuttal to a team test question where they disagree with the answer. I did try this for a couple of semesters, and for the most part students were not writing thoughtful reasons why they considered a question unfair, but were just trying to get points back. With so many teams in my class this part of the process was unmanageable for me and I stopped doing it.

This process works very well in a fully online synchronous class. Students take their iRAT as an online Canvas quiz due 10 minutes after the class start time. I usually allow the iRAT to be open earlier as online students frequently want more flexibility so it is easier to have a longer window rather than assign different times to particular students when you have a big class. Students can see their score after the iRAT but not which questions they got wrong.

The iRAT closes and the tRAT, also a Canvas quiz opens AFTER the iRAT closes. I do my class synchronously on Zoom and put students into breakout rooms where they each open the tRAT Canvas quiz and discuss the answers to the questions. They can be given multiple chances to submit this test so that by the end they know what the answers are. The only downside is that students tend to do more guessing.

I have had to make groups bigger when doing this online to account for the number of students that turn their cameras off and don’t participate. The process works well for the students that are engaged, but not so well for the disengaged ones.

If you are trying to avoid too much paper, you can have students do the iRAT online and then have them do the tRAT in class. The only downside is that I have found that it is too easy for students to cheat on the online tests and they come to the team work without enough knowledge to have a good discussion about the questions.

Flipped Classroom Strategies

The Readiness Assurance Process (RAP) and team assignments take a lot of class time. An iRAT and tRAT assessments can take close to 40 minutes and team assignments minimally take anywhere from 10 minutes to a whole class. This means that there is less time available for lecturing, so a flipped class format is ideal. Students are provided with clear learning objectives and materials to study ahead of time so that you don’t have to tell them everything during class. There are a number of benefits to this:

- Students can access content at their own pace. Sometimes students cannot keep up with the pace of a standard lecture course. Providing students with videos and notes ahead of time allows them to take notes and process information at a slower (or faster!) pace if needed.

- You use class time to do activities where students do more talking than the instructor and discover where they have misconceptions and where they simply need to study more before they have to take a high stakes assessment. Students tend to prefer interactive classroom activities to lectures (Bishop & Verleger 2013, Galway et al. 2014) so presumably are more engaged.

- When you listen to students explaining their reasoning for an answer on a tRAT or a team assignment, you learn why they choose their answer and are able to address misconceptions for the whole class that you never realized existed.

- Students direct where the class goes. You don’t have to “cover” everything so you can change direction and spend more time on topics that students are finding challenging.

- Lectures are simply not that effective (Knight & Wood 2005). The real learning does not happen while you are talking “at” students. It happens when they work through their notes, maybe adding in information from the textbook, and when they do homework assignments and quizzes.

A number of studies suggest that a flipped classroom model where students access content on their own and apply it during class activities results in higher learning gains in addition to improved student satisfaction (Akçayir & Akçayir 2018, Bishop & Verleger 2013, Enfield 2013, Galway et al. 2014). The collaborative learning that occurs during group activities allows students the opportunities to take risks and make mistakes as they become more adept at thinking like experts (Wallace et al. 2014).

There are a number of challenges involved with using a flipped classroom format and a balanced perspective is outlined in Rotellar & Cain (2016). Typically when students are asked to take more responsibility for their learning and be prepared for class by completing homework on time, they will perceive that they are “teaching themselves” and the instructor is not doing anything. Students may feel lost in what may appear to be a more chaotic classroom and feel that they are doing extra work. Faculty often have a hard time accepting that they do not have to say everything to students that needs to be learned. These challenges can be overcome with planning and organization.

For a flipped classroom to be effective, you must provide the following:

- Resources – High quality engaging study materials with clearly aligned learning objectives that students can use as their study guide. Without this, they do not know what to study as they don’t have a previous lecture as a scaffold for their learning.

- Accountability – Lack of preparedness is one of the greatest barriers to student learning in a flipped classroom (Akçayir & Akçayir 2018), so the team-based learning model with the RAP and peer review is an effective way to promote student preparedness and attendance.

- Engaging in-class activities – If students don’t perceive any value in attending class, they won’t come.

- Brief, purposeful lecture – A TBL class uses a small amount of lecture to explain difficult concepts in response to student difficulties.

- Metacognition opportunities – It is important to share with students how they learn and how your pedagogy is helping them to get there.

Example of Teaching Unit from Human Physiology, Elizabeth Tomin, Instructor

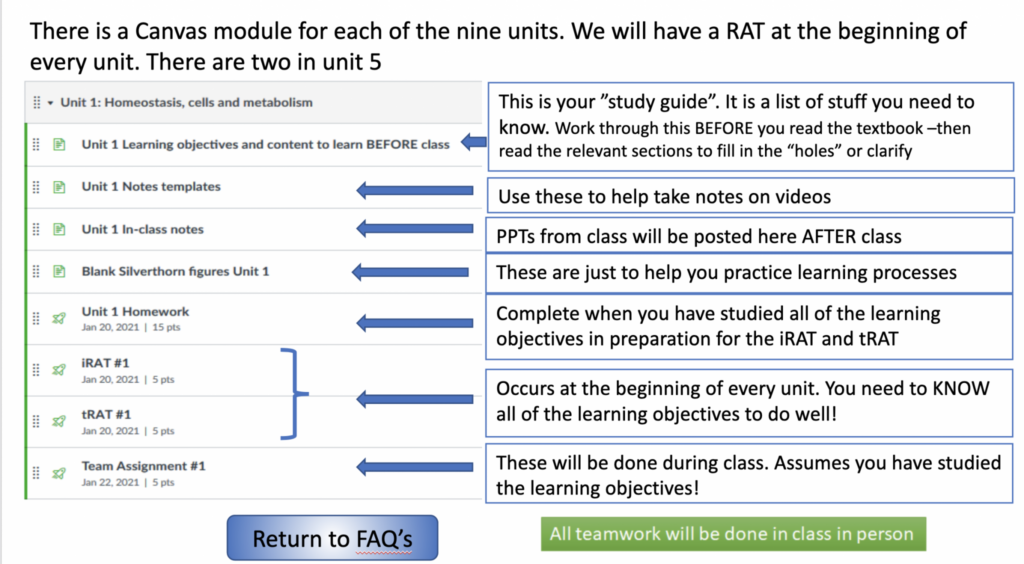

My human physiology course is organized into 9 units. Each unit starts with the RAP, which is then followed by class sessions that include discussion problems, clicker questions, team assignments and lecture/explanations interspersed throughout those activities. There are 4 summative tests during the semester, and Lecture Test 2 is an example of one of them.

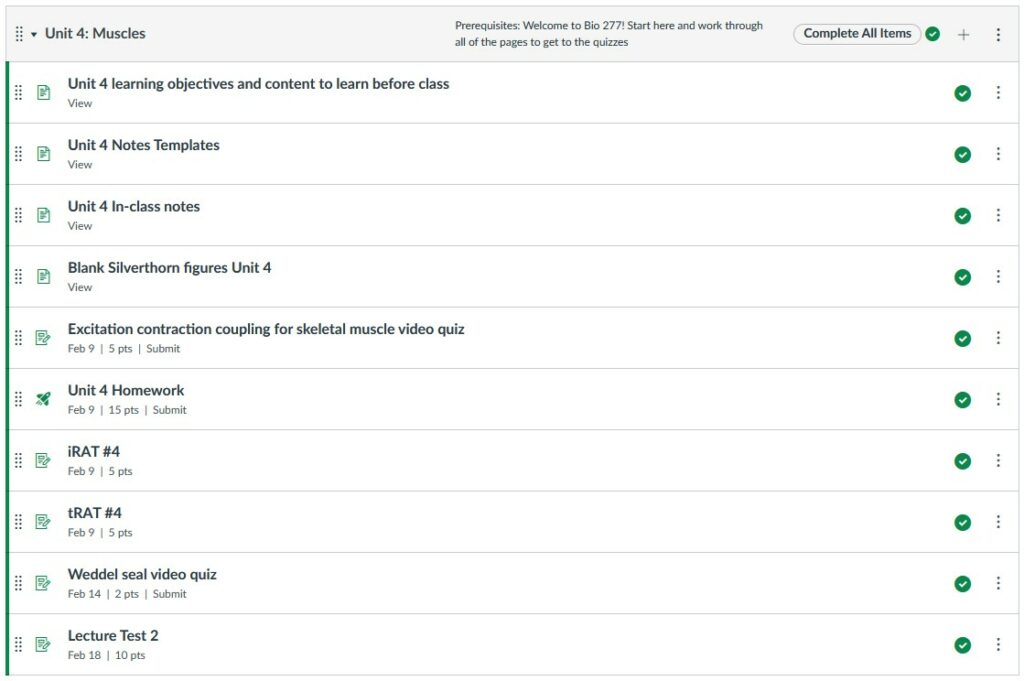

Each teaching unit is organized into a Canvas module. Each Canvas module follows the same pattern:

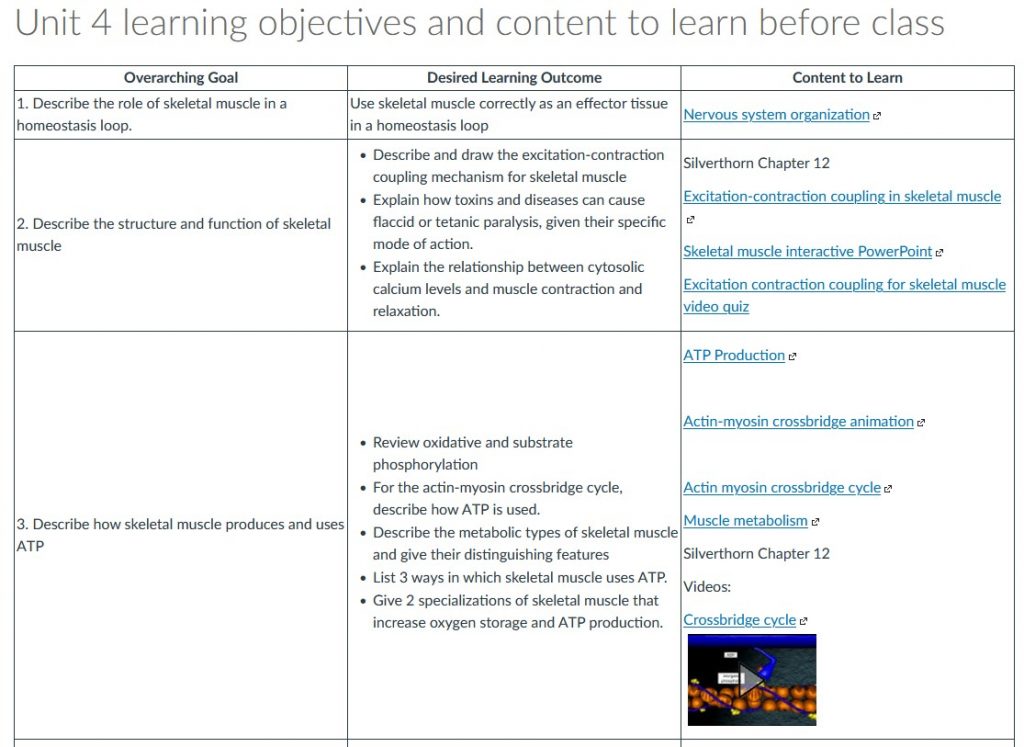

The learning objectives and content to learn before class provide the “study guide” for students. A portion of the Unit 4 learning objectives and content to learn are shown below.

Content to learn is provided in the form of PDF files, videos and interactive PowerPoints where the students can work through content in a more active way. Notes templates are provided so that students can take notes on key videos and practice writing out the processes.

It is emphasized to students that they need to study and learn the content provided in preparation for the RAP so that they are prepared for team work that follows. This way, students are able to discover what they don’t understand early on in lower stakes assessments.

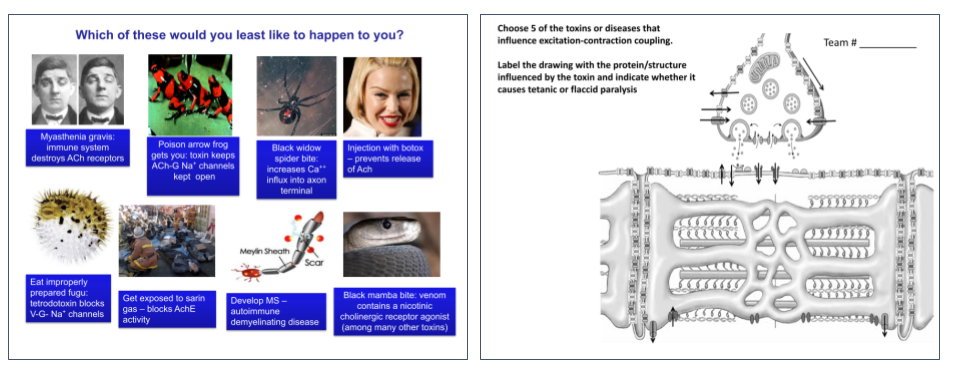

Example of a team assignment

In the Excitation Contraction Coupling session listed on the syllabus, students are given a small amount of lecture followed by the prompt on the left. The assignment on the right is included in their team folder.

Students must understand the whole process of excitation contraction coupling in order to predict the consequence of being afflicted by any of the given toxins or diseases. Choosing 5 means that students are repetitively going through the process which models how they need to study. They are reminded that by the end of this they should be able to predict the consequence of any toxin or disease if given the mode of action.

Active Learning Strategies

Active learning involves activities in the classroom other than taking notes and following directions where students are actively involved in the learning process (Handelsman et al. 2007). Knight & Wood (2005) found that students in large biology classes improved their conceptual understanding in classes where there was less lecturing and more active learning.

Testing and quizzing is often overlooked as a form of active learning. Roediger & Karpicke (2006) found that repeated testing of students resulted in dramatic improvements in longer term retention of content than repeated studying with less testing. They suggest that practicing the skills during studying that are needed for retrieval on an assessment result in enhanced performance on subsequent assessments of mastery. In disciplines where students are expected to apply content to problems it stands to reason then, that they need to practice these skills actively.

Michaelson & Sweet (2008) consider that assignments that promote both learning and team development to be one of the four essential elements of team-based learning. They stress the importance of activities that require teamwork rather than those where students divide up the jobs and work individually to produce a lengthy product. Examples include activities where a group decision or choice needs to be made based on discussion among the team members.

Active learning can be incorporated into classes in a variety of ways, ranging from short to fairly time consuming. Several of these are summarized in Handelsman et al. (2007) but here are examples of ones used most often. The decision about what type of activity to do and how to assess it depends to a great extent on the size of your class, number of teams, and the discipline that you teach. The Readiness Assurance Process (RAP) that is a foundation of team based learning is critical to the success of active learning activities because students need to be prepared with a baseline level of knowledge in order to participate in a meaningful way. The RAP itself is also a form of active learning!

Electronic Response Systems

Electronic response systems are great because they allow for very quick activities and if you are counting them for a grade, the process of recording grades is usually pretty automated. There are a number of different electronic response systems that can be used. Many systems such as iClicker allow remote access using an app in addition to the use of physical radio frequency clickers in the classroom. There are also a lot of publisher-based apps that allow a variety of different question types and activities. Response systems can be used in a number of useful ways.

- To check quickly where students are with respect to a concept.

- To generate discussion especially when a question with no right answer is asked. This is a good way to introduce a new topic or concept.

- To find and explore misconceptions. This involves asking a question in which you are pretty sure students will be split between two or more answers, show them the results, allow discussion and then ask the question again. Hopefully after peer discussion a much higher percentage of the students will get the question right!

Brainstorming

In this type of activity students are presented with a broad question or problem. It is a really useful way to discover what students already know, and provide teams with an opportunity to share their collective knowledge.

An example of Brainstorming from Elizabeth Tomlin:

An example I use is to ask them how a mammal such as the Weddell Seal can stay underwater for up to an hour without breathing. The answer that I am really looking for is related to muscle metabolism as that is the topic where this question is asked, but students come up with all kinds of other great ideas that allow for positive reinforcement of their application of prior knowledge to a new problem. This type of brainstorming can also be generated by asking a clicker question that has no completely right answer or multiple right answers.

Case Studies and Application Questions

Another type of team activity is a case study type where students are provided with a scenario where they then either have to make a treatment decision or draw some other type of conclusion based on the information given and what they know about the topic.

An example of Case Studies / Application Questions from Elizabeth Tomlin:

For example, they could be presented with a case of a patient on a ventilator that has been turned up too high for a period of time and decide how this would affect the plasma pH and potassium levels in the blood of the patient. This requires thinking through several processes before drawing a conclusion. Students might also be asked to draw or label something as their conclusion to a problem or interpret quantitative data. These have to be thought through carefully to make sure that the students are not able to “divide and conquer” but are truly working together. It goes without saying that it is also important if you have a large class with a lot of teams, to make sure the grading is manageable.

Collaborative assignments can be quite easily done in online classes. For synchronous classes breakout rooms in Zoom work well. Make the groups larger than normal for online work as many students do not turn on their cameras and participate as readily as they do in a face-to-face class. For asynchronous meetings, groups would need to organize meeting times for themselves for a true collaborative experience with back and forth discussion. For an online lab experience, consider having the groups meet once a week with the instructor and then meet on their own to complete assignments. Obviously there are limitations to class size that can be accommodated with this format.

Case studies or application questions can be presented as Canvas assignments, shared Google docs, Google Jamboards or using other types of collaborative software tools.

Use of Learning Assistants in Large Classes

Active learning in teams is really challenging in a large class. For example, Elizabeth Tomlin’s Human Physiology class has between 44 and 48 teams of 5 or 6 students and it is virtually impossible for her to answer everyone’s questions in a reasonable amount of time. One technique she uses is if she receives the same question more than once, she will ask the class to stop what they are doing and address the question to the whole class. This improves efficiency as generally most groups have similar questions about any given activity.

The best way to facilitate active learning in large classes though is to have some help. This could be in the form of graduate student assistants, your supplemental instruction leader if you have one, and other undergraduate learning assistants.

In the Biology department, we created a course called Science Pedagogy for Learning Assistants (Bio 496) which is a 1 credit hour practicum course. Students attend a one hour session each week where we discuss various aspects of active learning pedagogy, attend the class in which they are assisting, and spend about 30 minutes each week with the instructor of the course they are assisting so that they know what activities are coming up. The learning assistants help answer students questions during class time but also develop and lead an active learning activity in the class that they are assisting. In a synchronous online class, learning assistants are actually needed even more to move in between breakout rooms facilitating discussion.

How to create and manage teams

It is important for teams to be as diverse as possible, and the type of diversity might depend on what type of course you are teaching. When Larry Michaelson taught a workshop several years ago, he split the participants up based on the participants’ attitudes towards team based learning. Some instructors like to use a pretest method to collect data for the purpose of assigning teams.

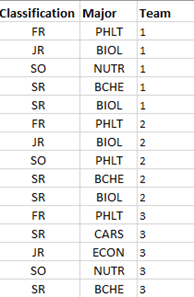

Example from Elizabeth Tomlin

For my large physiology class (up to 288 students in 48 teams) I use class and major. I have students that range from freshmen to post baccs and majoring in biology, chemistry, biochemistry, psychology, nutrition, kinesiology, therapeutic recreation, pre-nursing and a few others. I set up my teams ahead of time by class first and then by major to evenly distribute intellectual assets and liabilities. Below t is an example of team makeup for the first 3 teams with names omitted. Obviously racial and ethnic diversity is important, but my classes are already so diverse I don’t have to make any effort for teams to be diverse on that basis.

Once I have the teams prepared in an Excel file, I make “team number” a grade column in Canvas worth zero points so that I can sort the gradebook by team. I also set up Canvas groups under People so that students can communicate with their teams.

How to create groups in Canvas

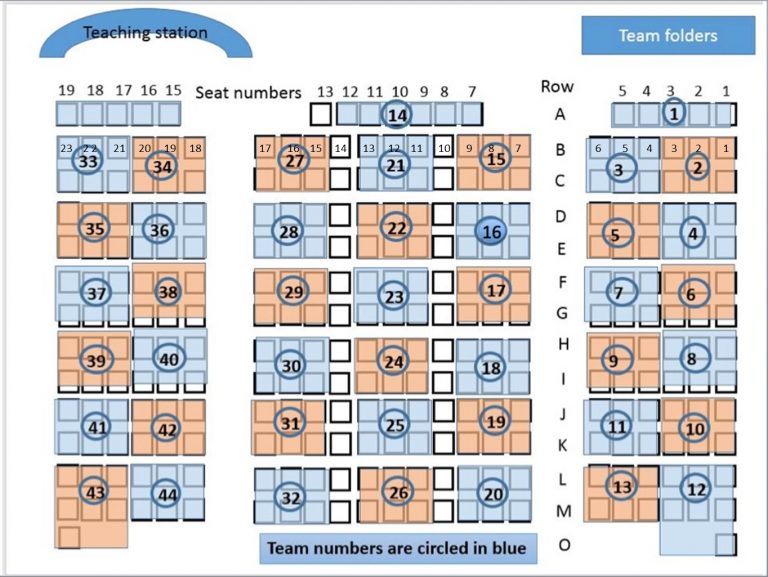

Once students are assigned to teams, I inform them via Canvas announcement that they can use the Group function on Canvas to see what team they are assigned to or look at the gradebook in Canvas. Each team is assigned to a seating area in the classroom and the seating map is posted on Canvas. This is a seating chart for 44 teams in Sullivan 101. Once students are in place on the first day, I have them record their seat coordinates so they know where to sit moving forward. With help from a couple of assistants, they are usually all in place about 5 minutes after the start of class on the first day!

Team Size

There is a lot of debate about how big teams should be. If they are too big, they tend to split into two factions and don’t work together and if they are too small there is a risk that they may not have the collective knowledge to solve problems on team tests and assignments. Larrry Michaelson says that 8 is the magic number where they tend to split in two, and 5-7 is the optimum size. I usually start with 6 students per team knowing that some teams will shrink a bit over the semester.

Permanent vs. Rearranging Teams

I keep my students in permanent teams. When I first started using team based learning, I asked the class halfway through the semester if they wanted to rearrange their teams and the response was overwhelmingly no. When in permanent teams students get to know each other and most work well together. The downside is that some teams don’t really work well together.

Managing Teams, Attendance, and Grading

I provide a pocket folder for each team which contains an attendance form stapled on the inside cover and whatever documents they need for the class. Students mark who is present and absent so that I know who gets credit for the team work. This is obviously an honor system, but generally I am alerted if there is an egregious abuse of the honor code. I also return work to the students in this folder. This system was very helpful when we had to keep seating charts for contact tracing.

Some instructors like to use response systems like iclickers to manage attendance, but students can “forget” to bring their clicker or not be able to connect to the wifi. If you have a small enough class you can always use the Canvas attendance feature.

Managing Teams in an Online Class

In a synchronous online class taught over Zoom, teams can work together in Zoom breakout rooms. I tend to make teams a LOT bigger when teaching online because so many students refuse to turn on their cameras and actively participate. It takes a group size of 10-12 to get 3-4 students to actually talk with each other. It is also important to move between breakout rooms to monitor discussion and ask students if they have questions.

Peer Feedback

Students frequently complain about group assignments because often there are “free riders” that are less prepared and do less work than other members of the group. In a team based learning class, team members must come prepared with the background level of knowledge to be able to solve a complex problem and make a decision as a team. As Michaelson & Sweet (2008) so bluntly put it “no amount of discussion can overcome absolute ignorance.” For this reason, students are more accountable to their classmates than in a typical lecture class.

It is important that team members have an opportunity to provide formative feedback to their peers. Over the course of a semester, students grow to rely on their team members to help them work through problems and in cohesive teams, they become motivated to not let each other down. Aim for around 3 peer evaluation surveys throughout the semester. Frequently, students will provide encouraging feedback to each other about how much better they are doing on the second peer feedback survey than on the first.

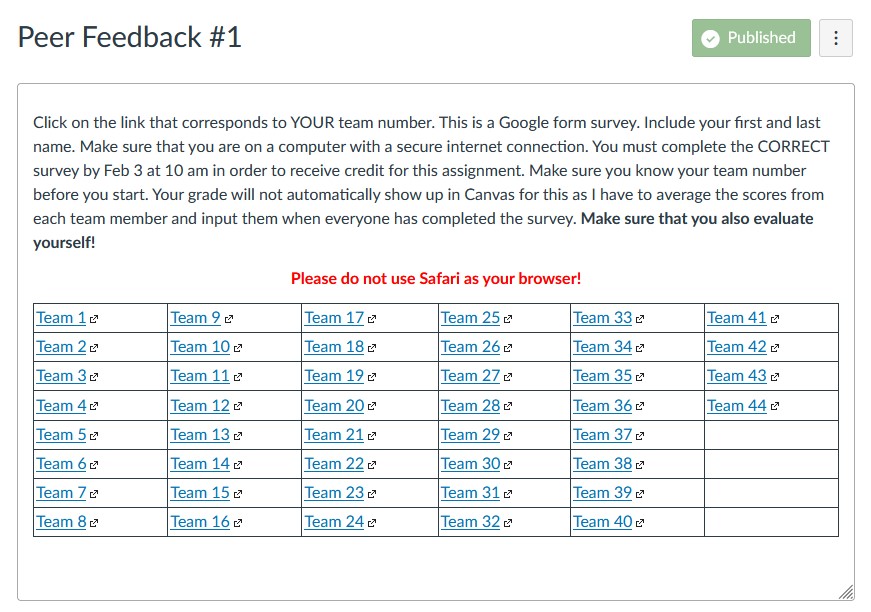

Consider doing your peer evaluation by using Microsoft forms. Make a separate form for each team and link them in a Canvas assignment. Students click on the link corresponding to their team number.

Include the name and email address of each team member ahead of time. Names should be preloaded because some students get confused about the names of their teammates. The email addresses are needed so that feedback can be returned anonymously to each student using a script in the Google results sheet.

Example of a peer evaluation form:

This shows how students provide their own name at the top, and then rank each team member, including themselves and provide some written feedback. This portion of the form is repeated for each team member and results returned to them using a script in the results file which automatically emails the written feedback to each student when the program is run.

Student Reactions to Team-Based Learning

Students have mixed reactions to Team-Based Learning (TBL) and it is important to “sell” it to them from Day 1 and follow up frequently with reminders about why learning actively in teams benefits them. I use this graphic on the first day and explain that physiology is a discipline that involves applying knowledge and concepts to solve problems, and that it is not just memorizing facts.

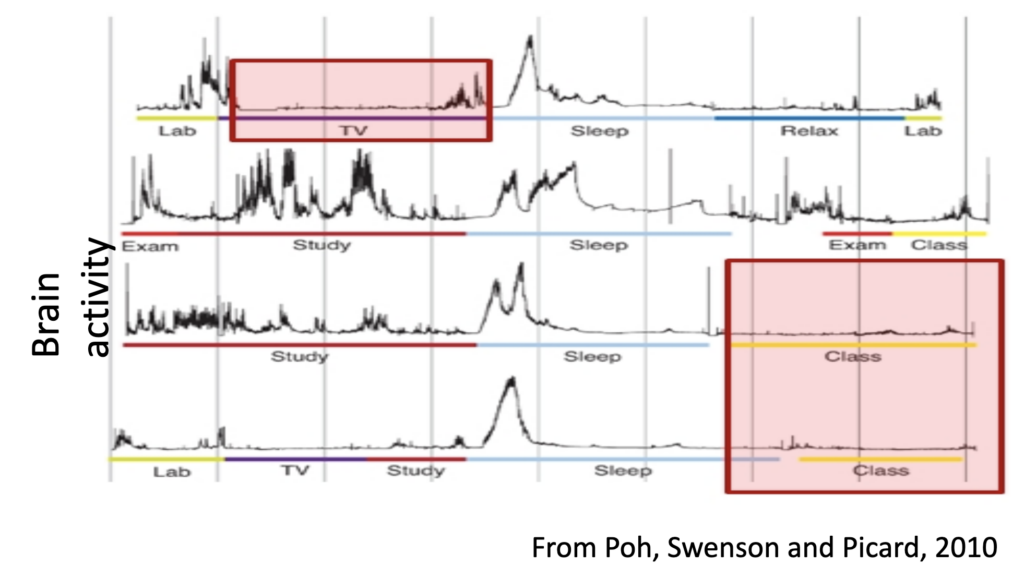

I show them this image from Poh et al. 2010 on the first day and talk about how little is actually learned during a lecture, and that there is a large body of literature that supports this.

Next I talk with them about how the course will go, and outline how the course is organized and explain WHY we do specific assignments. This is also covered in an introductory video in Canvas that walks them through the Canvas modules.

- YOU as a student work through and STUDY content that you access Canvas in various forms (videos, PDF’s PowerPoints), read the relevant part of the textbook, and complete your Canvas homework BEFORE you come to class!

- RAP: iRAT’s and tRAT’s. RAP is the readiness assurance process described in the syllabus. You need to STUDY for these tests and do as well as you can. Your goal is to be able to explain concepts to your team members. If you can teach something then you know it!

- Problem solving, brainstorming and discussion of concepts. A significant amount of class time will be devoted to discussion problems. If you participate you will learn!

- In-class team assignments. Participation in class assignments and discussions will help you figure out where you are confused or have misconceptions before a high stakes test.

Then I walk them through what is in each Canvas module and explain what they need to do with each page in the module to be successful.

Next, I explain the breakdown of grades. It is important to explain how the team work directly affects their grade, but also how it indirectly affects their individual grade by helping them learn how to apply content on their own.

The last thing that I usually talk about on the first day is how they will be assigned to their teams. Usually I wait until the 3rd day of class to put them in teams to account for the schedule adjustment period. I tell them that they are put in teams based on class and major so that teams include students with the broadest range of experience and knowledge possible. I also give them the opportunity to request specific areas in the room to sit as some students need an aisle seat, front, back etc.

Frequently Asked Questions

I think of a lecture as more of a summary of what you need to learn. Actual learning happens when you work with the content, applying it to solve problems such as in homework assignments and team assignments. It is important to provide high quality study materials for students to study outside of class with specific learning objectives, which allows you to spend more time in class applying and clarifying content.

I keep teams together for the whole semester and use peer evaluations for students to assess each other’s performance. It is extremely rare for students to say anything unkind about/to each other. All of the team work happens during class so there are no issues with students trying to get hold of each other to get work done. In the 8 years or so that I have been using Team-based learning, I have only had two team “divorces” where I redistributed students to different teams.

The use of peer evaluations with a score attached helps to motivate students to contribute to their team. In the end, you are relying on peer pressure to encourage students to contribute but there will always be some students that do not contribute much. I structure the grading so that their individual performance is the strongest predictor of their final grade.

There is a lot of metacognition involved here. I point out that students do not learn much during lectures and there is a large body of literature that supports this. I show them the graphic that is a measure of brain activity during various tasks, and it is lowest during lectures. I also explain that the real learning happens when students struggle with content on their own to apply it to homework problems or explain things to each other during team activities.

My course evaluations are bimodal. Students either love or hate team based learning, and it is important to have departmental support. I have had students email me later and tell me that they are so grateful that they took my class because they learned more than they had ever learned before and planned to apply the study strategies that they learned to subsequent classes. I keep those emails!

The readiness assurance process is the key to this. Students, despite their best intentions, will not study effectively enough to do the active learning activities if there is not a grade attached, at least in my experience.

I give 15–16 team assignments over the semester and only count the best 10. I also drop 1 team test. If students miss a team assignment or test with a valid excuse then I just give them an excused grade in Canvas.

This is a challenge. In biology we now have a class (Bio 496) which is Science Pedagogy for Learning Assistants. Students attend a seminar type class once a week where we discuss active learning and help answer questions during class time in the course in which they are assisting.

It is important to provide high quality study materials for students to study outside of class with specific learning objectives, which allows you to spend more time in class applying and clarifying content. I took the PowerPoints that I used when my class was in a traditional lecture format and made videos, Google Docs and interactive PowerPoints for students to use. These are linked with the learning outcomes.

I keep the same teams all semester. They get comfortable and efficient working with each other. When I first started doing team based learning, I asked the class half way through the semester if they wanted to shuffle teams and the answer was an overwhelming no.

Teams need to be big enough to provide enough breadth of knowledge and experience, but not so big that they fracture into two teams. It is also important to account for the possibility of students dropping the course. I have found that 5–6 students is an ideal number.

When you are ready to learn more about team-based learning, watch this recorded webinar from Elizabeth Tomlin, Ph.D. as she explains the process and answers faculty questions.

Team-Based Learning Collaborative

Team-Based Learning from Yale’s Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning

Team-Based Learning from Indiana University Bloomington’s Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

Introduction to Team-Based Learning on YouTube.

References

- Akçayir, G. & M. Akçayir. 2018. The flipped classroom: a review of its advantages and challenges. Computers and Education 126: 334-345.

- Bishop, J.L & M.A. Verleger. 2013 120th Annual Conference and Exposition. American Society for Engineering Education. Atlanta.

- Enfield, J.E. 2013. Looking at the impact of the flipped classroom model of instruction on undergraduate multimedia students at CSUN. TechTrends. 57(6): 14-27.

- Galway, L.P. K.K. Corbett, T.K. Takaro, K. Tairyan & E. Frank. 2014. A novel integration of online and flipped classroom instructional models in public health higher education. BMC Medical Education. 14:181.

- Handelsman, J., S. Miller & C. Pfund. 2007. Scientific Teaching. W.H. Freeman & Co.

- Knight, J.K. & W.B. Wood. 2005. Teaching more by lecturing less. Cell Biology Education. 4:298-310

- Koles, P.G., A. Stolfi, N. Borges, S. Nelson & D.X. Parmelee. 2010. The impact of team-based learning on medical students’ academic performance. Academic Medicine 85: 1739-1745.

- Michaelsen, L. K., Knight, A. B., & Fink, L. D. (2002). Team-based Learning. ABC-CLIO.

- Michaelson, L. K. & M. Sweet. 2008. The essential elements of team-based learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 116: 7-27

- Michaelson, L.K., N. Davidson & C.H. major. 2014. Team-Based Learning Practices and Principles in Comparison With Cooperative Learning and Problem-Based Learning. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 25: 57-81

- Parmelee, D., L. K. Michaelsen, S. Cook & P. D. HudesTeam-based learning: A practical guide: AMEE Guide No. 65. ISSN: 0142-159X (Print) 1466-187X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/imte20

- Poh, M., N.C. Swenson & R.W. Picard. 2010. A wearable sensor for unobtrusive, long-term assessment of electrodermal activity. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering: 57(5).

- Pollack, A. E. 2018. The neuroscience classroom remodeled with team-based learning. J. Undergraduate Neuroscience Education. 17(1): A34-A39.

- Roediger, H.L, III & J.D. Karpicke. 2006. Test-enhanced learning. Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science. 17 (3) 249-255.

- Rotellar, C. & J. Cain. 2016. Research, perspectives, and recommendations on implementing the flipped classroom. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 80(2): 1-9.

- Wallace, M.L., J.D. Walker, A.M. Braseby, & M.S. Sweet. 2014. “Now, what happens during class?” Using team based learning to optimize the role of expertise within the flipped classroom. J. on Excellence in College Teaching. 25(3&4):253-273.